Janis’ DreamsCome True atMonterey Pop

By Holly George-Warren

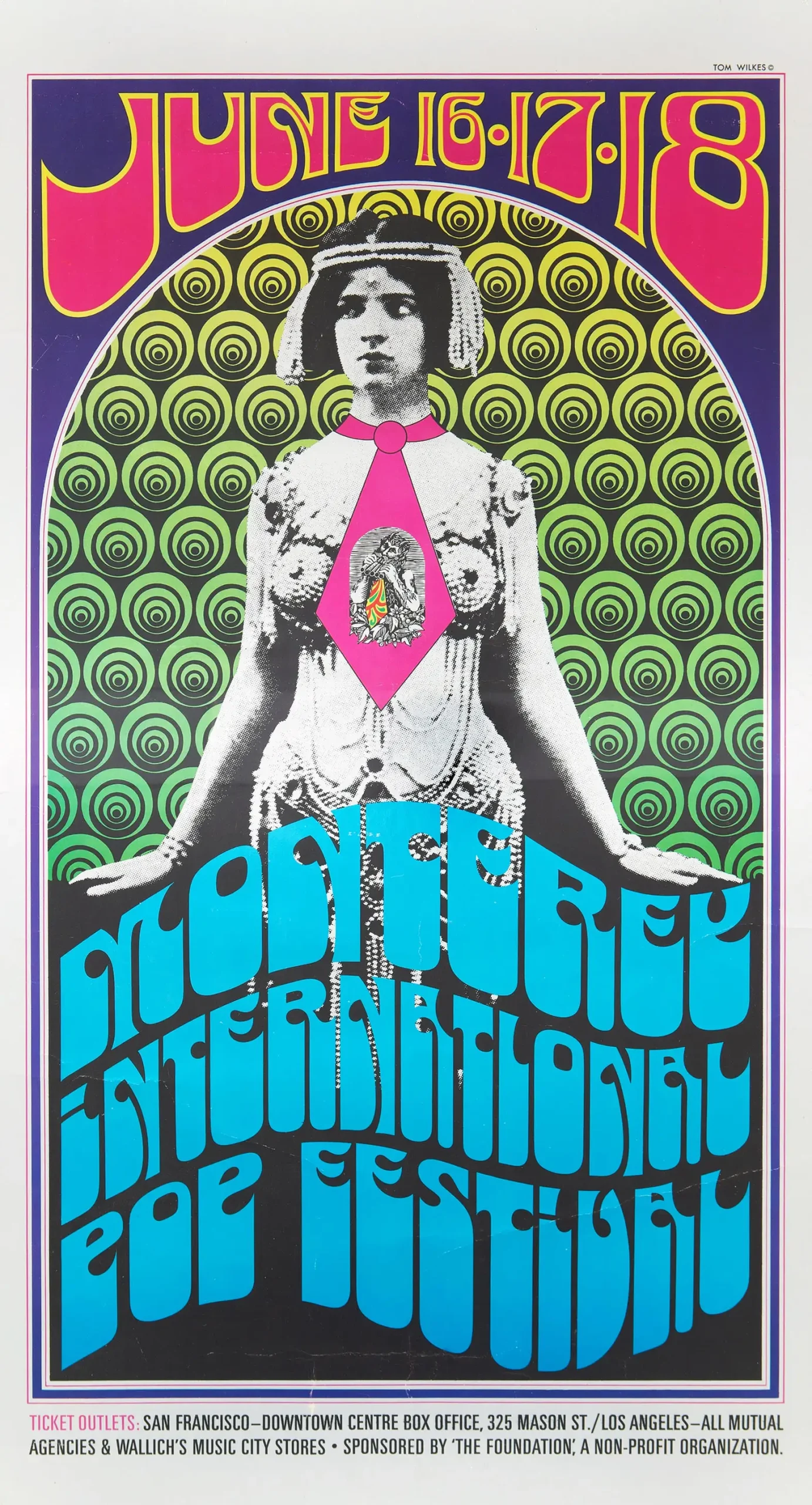

The groundbreaking Monterey International Pop Festival – June 16-18, 1967 – transformed Janis Joplin’s career while planting the seed for festivals like Woodstock.

Janis arrived at the bucolic Monterey County Fairgrounds as a member of Big Brother and the Holding Company (BBHC), largely unknown outside San Francisco.

By weekend’s end, she was the subject of global media attention and would be sought after by Columbia Records president Clive Davis and Bob Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman. On her way to superstardom, “the real queen of the festival” – as dubbed by one reporter – would be the highlight of D.A. Pennebaker’s celebrated 1968 documentary, Monterey Pop.

Four years earlier, during her original residency in San Francisco performing acoustic blues at coffeehouses, Janis had attended the Monterey Folk Festival, in May 1963. Wandering the grounds, she’d met her idol Bob Dylan, whose debut album had caught her attention. She approached him, introduced herself, and said, “I’m gonna be famous one day!” The gimlet-eyed troubadour replied, “Yeah, we’re all gonna be famous.” On those very same fairgrounds, Janis’ prediction would come true.

I’m gonna befamousone day!

Janis Joplin to Bob Dylan

In 1967, the Monterey International Pop Festival was the brainchild of producer and label exec Lou Adler and his partner John Phillips, founder of the Mamas and the Papas. Their team sought to enlist talent for a three-day festival where rock artists would play the kind of prestigious fest usually reserved for jazz or folk. The promoters offered to pay artists’ expenses but no performance fees; any profits would be donated to various charities. The festival’s Board of Governors included Paul Simon, and the fest’s PR director was former Beatles publicist Derek Taylor. Among the 33 acts booked to play a total of five concerts over three days were seven San Francisco bands, including BBHC, Grateful Dead, and Jefferson Airplane; L.A. pop stars like Phillips’ group, Johnny Rivers (a board member), and the Association; folk-rock stalwarts the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield, and numerous artists from England, New York, and elsewhere – among them, the Who, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Simon & Garfunkel, Otis Redding, and Ravi Shankar. Tickets for the recently refurbished 7000-seat arena ranged in price from $3 for bleachers to $6.50 for a folding chair in the ground-level orchestra section. Large areas were cordoned off for record executives, media, and VIPs, among them, actor Dennis Hopper; Rolling Stone Brian Jones; former Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico; and Mickey Dolenz and Peter Tork of the Monkees.

The festival brochure promised that “the matchless hi-fi sound system” would ensure that “the sound carries well beyond the arena into the strolling area.” Indeed, during soundcheck, David Crosby (who performed with the Byrds and subbed for Neil Young in Buffalo Springfield) gleefully commented: “Oh groovy, a nice sound system at last!” Renowned engineer Wally Heider was enlisted to record all the bands’ sets.

Derek Taylor issued 1,100 media tickets, with about 100 journalists at a time squeezing into the press area. Phillips and Adler had flown in thousands of Hawaiian orchids, symbolizing the fest’s theme “Music, Flowers and Love” spelled out on a banner below the stage. Opening night featured L.A.’s polished popsters, with the sole black performer Lou Rawls promising “rock and soul,” U.K. blues shouter Eric Burdon and his new Animals singing about San Francisco, and Simon and Garfunkel capping the evening.

On the 24-acre fairgrounds, bands mingled with attendees – some decked out in hippie finery, others in short hair and crewnecks. An estimated 200,000 people, according to the promoters (though news reports put the number at 80,000), eventually arrived over the course of the weekend to wander the fairgrounds. “Those were real flower children,” according to Janis. “They really were beautiful and gentle and completely open.” Also attending were a smattering of Hell’s Angels, who’d previously been banned from the county. Local police, who’d feared their presence, were surprised by the bikers’ laid-back vibe, as well as the crowd’s congeniality.

“Never before had so much fine rock & roll been assembled in the same place,” wrote Ellen Sanders, who arrived from New York with fellow scribes Richard Meltzer and Sandy Pearlman. “There was this feeling when you walked through the gates – the delight of seeing performers, spectators, even the cops, with those silly bewildered grins on their faces, milling about, conversing easily, sharing sandwiches, fruit, shop talk, or nodding knowingly and happily to one another.”

“We stayed on-site all day and night,” recalled BBHC drummer Dave Getz, “backstage, eating, drinking, watching the other groups, sometimes from the side of the stage or from a reserved section in the front. I saw every performance.”

Definite B-listers, Big Brother were slotted to go on second during the Saturday afternoon concert, deemed “underground day,” and mostly including other Bay Area groups like Quicksilver Messenger Service and L.A.’s newly formed blues band, Canned Heat.

Hardly anyone outside the Bay Area had seen Big Brother and the Holding Company perform live. “Janis was so nervous, it was crazy,” John Phillips remembered. “Backstage, Lou Rawls was telling her, ‘It’ll be fine. Don’t worry about a thing.’ She was rattling, just shaking. But then just as soon as she hit that stage, she just stomped her foot down and got real Texas.”

BBHC’s former manager and Janis’ old friend from Austin, Chet Helms, introduced the band, singling her out: “Three or four years ago, on one of my perennial hitchhikes across the country, I ran into a chick from Texas by the name of Janis Joplin. I heard her sing, and Janis and I hitchhiked to the West Coast…A lot of things have gone down since, but it gives me a lot of pride today to present the finished product – Big Brother and the Holding Company!”

The gospel-tinged “Down on Me” kicked off their set, with Janis’ confident vibrato immediately engaging the crowd. Performing numerous afternoon concerts in Golden Gate Park had prepared Janis and the band for this moment. “You looked and wondered, ‘What is this girl all about?” Lou Adler later reflected. “Where did she come from, looking like that and leading this all-male band?”

Janis opened “Combination of the Two” with her rhythmic scratching on the güiro alongside Sam Andrew’s guitar solo, followed by her joyful whoops, as Andrew sang his ode to San Francisco. Janis’ soaring scatting sailed along between the verses; the audience remained riveted as guitarist James Gurley played an edgy solo to close the number before Janis’ Otis Redding-inspired, “We’re gonna sock it to ya!” and soprano vocalizing. Big Brother immediately segued into the chaotic avant-rock number, “Harry,” and finished it before the audience could figure out what hit them. Bassist Peter Albin, at the mic to introduce each song, signaled the start of “Road Block.” Backed only by Getz’s drums, Janis and Albin’s voices blended well on the folky intro, “trying to find my road”: Then as the tempo picked up, Albin took over lead vocals with Janis’ call and response “Road Block” adding energy.

For their last number, Gurley let loose his long, twisted guitar lines to the Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton song, “Ball and Chain.” Transported, as if not singing to thousands, Janis, eyes closed, softly began the opening lines, building to a scream and paroxysms of emotional catapults toward the chorus. Emotional feedback from the totally engaged audience seemed to push her further, as she used dynamics and pauses that jolted them from their seats, ecstatically applauding. Her vocal acrobatics sounded natural, led by her feelings, not planned or contrived. Going from bell-like to vibrato to fervently testifying, “TELL ME WHY!,” Janis wrung every ounce of emotion from the song as she stomped her foot in time with the words, ending the bloodbath with “I’m gonna love you til the day I die….” While Janis softly intoned the titular line, explosive applause drowned out the sound.

“It was if the earth had opened up,” wrote Joel Selvin in his chronicle of the festival. “The audience was spellbound, startled at the crude power unleashed…She was the first real hit of the festival, a taste of what everybody had come to see.” Captured on film by Pennebaker, Mama Cass Elliott’s stunned expression and lips mouthing the word “WOW” epitomized the effect. “She had everybody riveted,” said Cass, who’d been sitting in the audience. “I’d heard from David Crosby about this girl from Texas who could sing her ass off. And I’d never seen anybody work without a bra before. She was sexy. It was an electrifying performance.”

“When she came off stage, she was crying,” Phillips recalled. “She couldn’t believe she’d gone over so well. It was such an emotional experience for her. Janis stole the show – she just took it!”

What Pennebaker and his camera crew did not capture was Janis and the band’s actual performance. The producers had hired the 35-year-old auteur of the Dylan documentary Dont Look Back to make an ABC-TV “Movie of the Week,” for which the network would pay 400 thousand dollars. BBHC’s manager Julius Karpen, suspicious of being ripped off by L.A. “sharpies,” had refused to sign the release form, handed to them minutes before they went onstage. Since the bands were performing gratis, Quicksilver and the Dead’s managers likewise wouldn’t allow their groups to be filmed without being paid or given creative control over the footage. But Pennebaker, a New Yorker by way of Chicago, was determined to get Janis in his film.

and my hair stood on end

“She came out and sang, and my hair stood on end,” Pennebaker recalled. “We were told we weren’t allowed to shoot it, but I knew if we didn’t have Janis in the film, the film would be a wash. Afterwards, I said to Albert Grossman, ‘Talk to her manager or break his leg or whatever you have to do, because we’ve got to have her in this film. I can’t imagine this film without this woman who I just saw perform.”

As Country Joe and the Fish hit the stage for a lackluster set, Janis was approached by John Phillips, who told her the band could play again Sunday night if they agreed to sign the contract permitting filming. Grossman, whose clients Paul Butterfield and Mike Bloomfield also performed on Saturday afternoon, was backstage, and Janis ran over to ask him, “Should we allow ourselves to be filmed for the ABC movie?” The 46-year-old manager known for his shrewd deal-making said simply, “Yes, I think you should.”

“We were in a quandary,” Andrew recalled. “Julius said, ‘No way you’re gonna sign this! You’re not going to be filmed!’”

Over several hours, Janis became more frantic, determined to talk the band into agreeing to be filmed. “It was Janis pleading her case, then Julius pleading his case,” Getz recalled. “All these meetings – Janis would talk to us, then she’d talk to Albert. Then we’d meet with Julius. It came down to almost a face-off between Janis and Julius. She said, ‘We have to be in this movie, and if it means getting rid of Julius, so be it.’” The band eventually “saw that being filmed was more important than whatever money was going to come out of it,” according to Andrew. And their manager, who’d been so proud of Big Brother during their set that he “had tears in his eyes like a proud papa, acquiesced to the band, against his better judgment.”

It was decided: Big Brother would play again the last evening of the festival. “Later that afternoon,’” recalled Pennebaker, “Janis came running up to me and said, ‘It’s all set, I’m going to do the performance again and you can film it.’”

As the matinee concert continued, with Al Kooper (a Dylan sideman who’d just quit New York’s Blues Project), the Steve Miller Blues Band, and Electric Flag (who debuted at Monterey) garnering interest, the buzz among the throngs focused on Janis and Big Brother: “I was in the front row, the press section,” recalled Richard Goldstein, acknowledged as the first rock critic, thanks to his “Pop Eye” column in the Village Voice, which debuted in 1966. “[Robert] Christgau was sitting right next to me. When we saw her, we were knocked over. From the first notes, her voice stunned me with its primal drive…I knew instantly that Janis would be a big star.”

The usually cynical Christgau would write in his Monterey coverage for Esquire: “The first big hit was Janis Joplin…a good old girl from Port Arthur, Texas, who may be the best rock singer since Ray Charles…with a voice that is two-thirds Bessie Smith and one-third Kitty Wells, and fantastic stage presence… She got the only really big non-hype reaction of the weekend, based solely on her sweet, tough self.”

Record label execs also took notice, including Columbia Records’ new president Clive Davis, who traveled from New York and who’d make his first signings based on that weekend. “I was told there would be new artists during the day, so I didn’t know what I’d be seeing and hearing,” Davis recalled. “Of course, the whole atmosphere, the whole spirit in the air, was of revolutionary proportions on a far bigger scale than I ever could have imagined before I went. Janis had no billing – it was just Big Brother and the Holding Company. She was absolutely riveting and hypnotic and compelling and soul-stirring in such a way that she clearly was representative of an epiphany that changed the rest of my life.”

After the Saturday matinee, a diverse roster performed the nighttime concert, ranging from Moby Grape to South African trumpeter Hugh Maskela, newcomer Laura Nyro (whose cabaret-style act was booed) and the Byrds, with Roger McGuinn miffed by Crosby’s political comments between songs. A chilling rain developed during the evening, delaying the set by Jefferson Airplane, who’d just had a Top Five hit with “Somebody to Love.” Finally, they played a hypnotic concert mostly in darkness except for a projected light show.

Saturday night’s climax was Janis’s favorite set of the weekend: Otis Redding, reaching an audience who’d not yet experienced his bracingly soulful sound. Janis had seen him at the Fillmore, and since then he had successfully toured Europe, backed by superb Stax house band, Booker T and the MGs, and the Mar-Keys horn section, both of whom accompanied him onstage. “SHAKE!,” Redding demanded, and the audience leapt to their feet for the first time since “Ball and Chain.”

On June 19, the Sunday matinee featured a three-hour concert devoted solely to Ravi Shankar’s trio, which exposed Indian music to most of the audience for the first time. His work was so unknown that his concert was the only one not to sell out in advance.

Finally, Sunday evening, after a workmanlike set by New York’s Blues Project, Big Brother returned to the stage, this time introduced by Tommy Smothers. With a pair of matching flared leggings added to the clingy white mini-dress with sparkly gold threads she’d worn on Saturday, Janis glowed in the lights. She lined her blue eyes with kohl and fluffed her hair out around her shoulders. The band was given half as much time as before, with Pennebaker requesting “Combination of the Two” and “Ball and Chain.” Those who saw both shows declared the second inferior to the first, but the film crew’s cameras documented a powerful performance.

“When you see what she does at Monterey when she sings ‘Ball and Chain,’ Pennebaker later said, “it was so amazing, yet so simple. … She just took that song to the cleaners.” Bob Neuwirth, working with Pennebaker that weekend, recalled, “Watching her perform was like watching a great violinist – it was the reaching for the notes that held the drama.”

Afterwards, Janis skipped off the stage, ebullient, hopping up and down when she reached the wings. The night’s concert proceeded with a meandering set by the Dead, sandwiched between explosive performances by the Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, their stage pyrotechnics shocking the audience. The Who and Hendrix had been recommended to Adler and Phillips by Paul McCartney.

The consensus of the weekend, though, was that Janis “stole the show,” according to John Phillips. “She just took it!” In Lou Adler’s estimation, “Otis Redding got their souls, and Ravi Shankar drove them out of their seats. Janis tore their hearts out.”

Monterey marked a drastic change for Big Brother. Grabbing the attention of heavy hitters like Grossman and Davis, and becoming the focus of festival media coverage, Janis had been singled out. She was no longer “one of the boys in the band,” as she’d happily considered herself over the past year. Like most journalists, Richard Goldstein applauded Janis, rather than the group – even referring, years later, to her bandmates as “sidemen” who “focused on Janis, cradling her with their riffs and coaxing her vocal flights.”

Back in San Francisco, she had become famous not only among her friends who saw her perform at the Avalon Ballroom or in the park, but among those who read newspapers and watched TV news. On Monday morning, the San Francisco Examiner reported that “In an encore performance last night,” Janis “repeated her triumph Saturday afternoon.” The paper’s front-page headline: “Dreams Come True in Monterey.”

(adapted from Janis: Her Life and Music, Copyright Holly George-Warren, 2019)

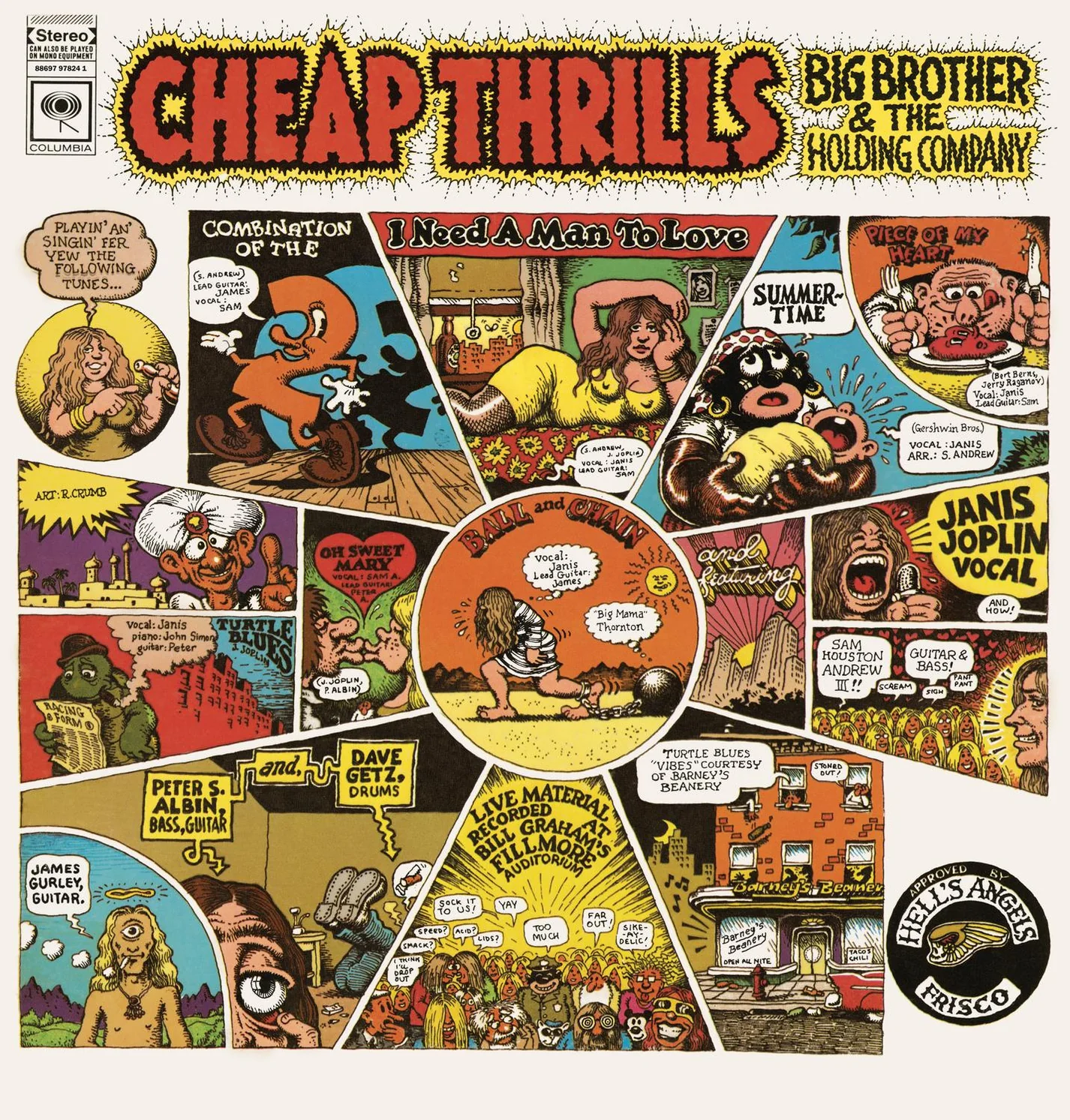

Monterey Pop helped elevate Janis and Big Brother to a national level. Shortly after, the band’s major label debut, Cheap Thrills, was released in 1968.

Janis and Big Brother’s rendition of “Ball and Chain” was also captured by filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker for his documentary film about the festival titled Monterey Pop.

Janis Joplin & Big Brother and the Holding Company 6/17/67 setlist:

- “Down on Me”

- “Combination of the Two”

- “Harry”

- “Roadblock”

- “Ball and Chain”

Janis Joplin & Big Brother and the Holding Company 6/18/67 setlist:

- “Combination of the Two”

- “Harry”

- “Ball and Chain”